Camilla Vuorenmaa’s third solo exhibition at Helsinki Contemporary titled Amuletti (amulet in Finnish) explores the relationship between humans and nature, shared rituals, and the symbolic power of amulets. Working across wood carving and painting, Vuorenmaa creates colourful, richly layered works, some of which extend into the gallery space as immersive installations. This exhibition marks the first occasion on which her wood sculptures are presented publicly.

The artist’s new body of work draws inspiration from Vuorenmaa’s recent stay in Kobe, Japan. During an artist residency, she engaged closely with Shintoism and the tradition of omamori amulets – objects believed to offer protection and bring good fortune. Shintoism embraces a worldview in which deities inhabit natural elements such as trees, rocks, and mountains. Affinities can be identified between Japanese beliefs and ancient Finnish folklore, which likewise regarded nature as sacred. Vuorenmaa’s recent works reflect on whether this sense of sacredness still resonates today, while acknowledging that humanity’s relationship with nature has long been marked by contradiction and subjugation.

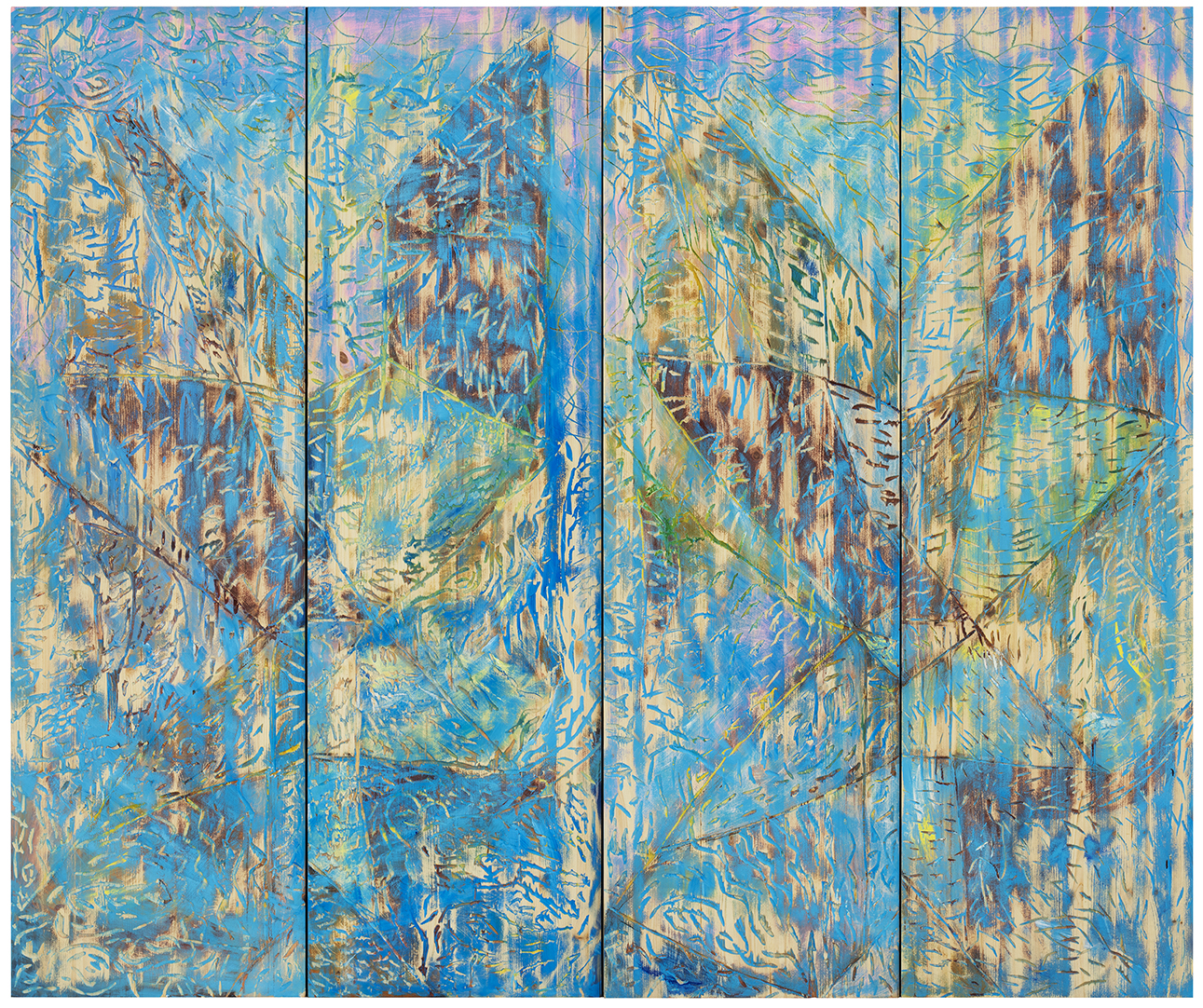

While informed by Japanese tradition, Vuorenmaa’s works also address broader questions of coexistence, community, and the pursuit of a meaningful life. She is particularly interested in how an object can acquire the status of an amulet, and how repeated gestures can evolve into private or collective rituals. Human figures play a central role in her practice, which is characterised by a compelling narrative and psychological dimension. In her new works, however, landscapes assume a more prominent presence alongside human figures. Her paintings recall Romantic imagery, where humans are embedded within the landscape and natural phenomena become symbolic reflections of human nature.

Like amulets, works of art signify more than their mere physical form: they are vessels of emotion, carriers of meaning, and sites of heightened presence. In Vuorenmaa’s practice, carving and painting alternate in a reciprocal process, each informing the other. The use of wood and rough, three-dimensional surfaces lends the works an artefactual quality, forging an inseparable connection between the material and subject matter.

Thank you to Finnish Cultural Foundation, Arts Promotion Centre Finland, Oskar Öflunds Stiftelse and Alfred Kordelin Foundation for supporting the artist's work.

Online viewing room on Artsy

Inquiries: info@helsinkicontemporary.com

In Discussion: Camilla Vuorenmaa & Minna Eväsoja, Wednesday February 11 at 5– 6 pm

Camilla Vuorenmaan kolmas yksityisnäyttely Helsinki Contemporaryssa käsittelee luontosuhdetta, jaettuja rituaaleja ja amuletteja. Vuorenmaa luo monikerroksisia ja värikkäitä teoksia, joissa hän yhdistää puukaiverrusta ja maalausta. Osa maalauksista laajenee galleriaan installaatioiksi. Näyttelyssä on ensi kertaa mukana myös Vuorenmaan puuveistoksia.

Vuorenmaan uusien teosten syntyyn on vaikuttanut taiteilijan viettämä aika Kobessa, Japanissa. Taiteilijaresidenssissä hän perehtyi shintolaisuuteen sekä onnea ja turvaa tuoviin omamori-amuletteihin. Shintolaisuus on japanilainen uskonto, jonka mukaan eri jumaluudet asuvat luonnossa, esimerkiksi puissa, kivissä ja vuorissa. Uskomukset muistuttavat jossain määrin suomalaista muinaisuskoa, jossa luontoa on pidetty pyhänä. Vuorenmaa on pohtinut muun muassa, minkälaisia jälkiä näistä pyhyyden kokemuksista on nykyajassa, ja sitä, miten suhteemme luontoon on ollut aina täynnä ristiriitoja ja myös luonnon alistamista.

Japanilaisesta kulttuurista ammentavat teokset laajenevat käsittelemään yleisemmin ihmisen suhdetta luontoon, yhteisöllisyyttä, sekä sitä, miten tavoittelemme hyvää elämää. Taiteilijaa on kiinnostanut se, miten esineestä voi tulla amuletti ja miten eleestä voi syntyä yksityinen tai yhteisöllinen rituaali. Vuorenmaan teoksissa on aina esiintynyt ihmishahmoja, ja niissä on vahva tarinallinen ja psykologinen vire. Uusissa teoksissa myös luonto ja maisema ovat ottaneet tärkeän roolin. Maalauksissa voi nähdä romantiikan ajan taiteen kaikuja: ihminen on osa maisemaa ja luonnonilmiöiden kautta kuvataan myös ihmisluontoa.

Kuten amuletit, myös taideteokset ovat aina enemmän kuin niiden fyysinen olomuoto: ne ovat objekteja, joihin on ladattu tunteita, viestejä ja läsnäoloa. Vuorenmaan teokset syntyvät prosessissa, jossa kaiverrus ja maalaaminen vuorottelevat ja tukevat toisiaan. Puun käyttö ja teosten rouhea, kolmiulotteinen pinta tekevät maalauksista esinemäisiä ja luovat erottamattoman yhteyden teosten aiheiden ja materiaalin välille.

Kiitos Suomen Kulttuurirahastolle, Taiteen edistämiskeskukselle, Oskar Öflunds Stiftelselle sekä Alfred Kordelinin säätiölle taiteilijan työskentelyn tukemisesta.

Näyttelyn online-esittely Artsyssa

Tiedustelut: info@helsinkicontemporary.com

Keskustelu: Camilla Vuorenmaa & Minna Eväsoja, keskiviikkona 11.2. klo 17–18

Share this exhibition