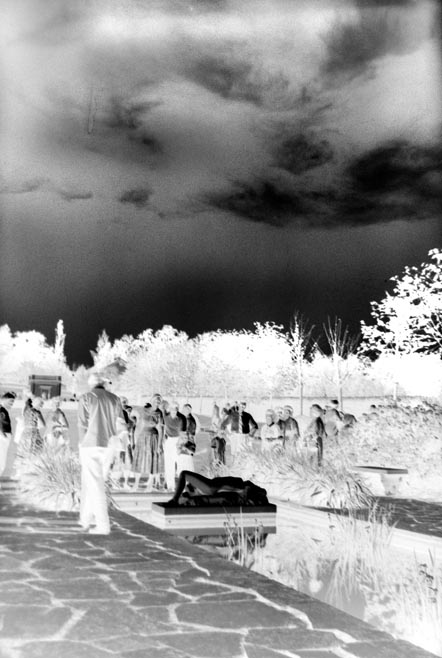

Helsinki Contemporary has the pleasure to present the first solo exhibition of the Swedish artist Annika von Hausswolff at the gallery. The title of the exhibition, Time Out Photography And About, characteristically both describes and defines the content of the completely new series of works.

In this exhibition Annika von Hausswolff focuses on the crucial issue of contemporary image making, in her works confronting a pair of existential and deep-seated questions: what is a photography about? And how do we keep on making images after moving from analog to digital technology?

“Reflections upon the tools of image making have always been in my mind since I started out with photography. Of course the transition from analogue technique to its digital successor has amplified the urge to understand the evolution of our visual culture. Looking at certain implements used for analogue image making, but also certain key aspects of photography itself – for example, its ability to mirror reality – I have made a series of images that all, in one way or another, relate to analogue image making. Some works, like the contact sheets of light, have a very conceptual point of departure, while others – for example, the self-portrait – deal more with the connection between photography and death.”

With the new series Annika von Hausswolff is literally re-visiting the tools of the trade that were central in the processes of analogue photography. She has produced images or objects from these no longer used materials. With the chosen strategy of “poetic justice” she has given these almost historical items a new life that cannot be reduced to their original function, but given them a completely new temporality and textuality – not to forget sensibility.

“It is impossible to imagine our existence today without the possibility of representing the world around us. The indexicality that is so typical for the photographic technique is unique, and although we understand more and more about its tampering with reality, it is still this powerful tool of presenting, representing, informing and reflecting our lives and space.”

“For an artist integrity is everything. Either it is about speed, or slowness. To me, ideas come with the speed of light, then it could take years to carry them out. When the images/ideas go public they start to exist in a different logic where I am no longer participating. It is like cutting off your fingers, again and again.”

“I believe the whole photographic apparatus to be saturated in mechanisms of desire. When you depict something there is a movement of getting closer as well as distancing yourself from the subject matter. It is a complex ritual of creating desire both within the witnessing subject and the reflecting object.”

This set of works again achieves this dual task. They demonstrate a painstakingly and accurately conducted genealogy of a medium, from a very personal and committed perspective, certainly depicting the demise of an industry. Simultaneously, this is achieved with a decisive and dedicated reflection that lacks any hint of one-way instrumentalization, silly nostalgia or cheap sentimentality.

Instead, it is a series of works that burns and heals, pushes and pulls, caresses and could not care less. It is a series that do the ultimate thing we can ask from works of art: they remind us what it means to be alive and kicking – kicking with pleasure, gusto and stamina against the pricks.

Quotations are from a conversation text between Mika Hannula and Annika von Hausswolff

Annika von Hausswolff is a Swedish artist who was born in 1967 and completed her formal art studies in the mid-nineties. Exploring different visual strategies within the field of photography, she has participated in numerous group shows and done many solo shows in Europe and North America, for example It All Ends With a Beginning at ARoS Aarhus Kunstmuseum, 2013, and Ich bin die Ecke aller Räume, Magazin 3, Stockholm, and Turku Art Museum, 2008. Her work revolves around existential and spatial issues in a conceptual yet formal manner. For the past five years she has been professor for the master's students in photography at Gothenburg University in Sweden.

Helsinki Contemporarylla on ilo esitellä ruotsalaistaiteilija Annika von Hausswolffin ensimmäisen yksityisnäyttely galleriassa. Näyttelyn nimi Time Out Photography And About luonteensa mukaisesti sekä kuvaa että määrittelee uusien teosten sisältöä.

Annika von Hausswolff hahmottaa yhtä olennaisimmista teemoista kuvan tekemisessä, esittämällä hyvin syvälle luotaavan sarjan kysymyksiä: Mistä valokuvassa on kyse? Ja miten kuvan tekemisen käytäntö muuttuu siirryttäessä analogisesta digitaaliseen tekniikkaan?

”Valokuvan teossa käytettyjen välineiden kriittinen tarkastelu on ollut aina keskeinen osa teoksiani. Tietysti siirtymä analogisesta digitaaliseen tekniikkaan on korostanut tätä halua ja tarvetta ymmärtää visuaalisen kulttuurimme kehitystä. Tarkastelemalla tiettyjä analogisen kuvan tekemisen välineitä, mutta myös tiettyjä valokuvaan liittyviä keskeisiä asioita, esimerkiksi sen kykyä peilata todellisuutta, olen tehnyt sarjan kuvia, jotka tavalla tai toisella liittyvät analogiseen tapaan tehdä valokuvia. Joissakin kuvissa, kuten teoksessa valokuvapaperiarkeista, on hyvin käsitteellinen lähtökohta. Toiset taas, esimerkiksi omakuva, hahmottavat valokuvan ja kuoleman välistä suhdetta.”

Uudessa teossarjassaan Annika von Hausswolff kirjaimellisesti sekä purkaa auki että nostaa esille analogisen valokuvauksen keskeisiä työvälineitä. Hän on työstänyt kuvia tai objekteja näistä jo syrjään siirretyistä materiaaleista. Valitsemallaan strategiallaan, jota voi kutsua myös ”poeettiseksi oikeudenmukaisuudeksi”, von Hausswolff on antanut näille lähihistorian esineille uuden elämän; elämän, jossa niitä ei voida palauttaa alkuperäiseen funktioon, vaan ne ovat saaneet ja saavuttaneet aivan uuden ajallisuuden ja koskettavuuden.

”Meidän on nykyisin mahdotonta kuvitella olemassaoloamme ilman mahdollisuutta esittää ja kuvata sitä. Valokuvan indeksi, suora yhteys kuvan ja todellisuuden viittaussuhteissa on ainutlaatuinen. Ja jos vaikka nykyisin tiedostammekin paremmin valokuvan mahdollisuudet työstää ja manipuloida todellisuutta, se on silti yhä voimakas väline käsitellä ja kuvailla, pohtia ja esittää itseämme ja ympäröivää todellisuuttamme.”

”Taiteilijalle kaikkien tärkeintä on integriteetti. Tekeminen liittyy joko nopeuteen tai hitauteen. Ideani syntyvät valon nopeudella, mutta niiden toteuttaminen voi kestää vuosia. Kun kuvat ja ideat päätyvät esille, niille kehittyy aivan oma minusta riippumaton logiikkansa. En ole enää osa niiden maailmaa. Se on joka kerta kuin leikkaisi sormiansa irti, yhä uudestaan ja uudestaan.”

”Väitän, että koko valokuvan olemus on täyteen ladattu halun mekanismeilla. Kuvaustilanteessa tapahtuu sekä lähestymistä että irtiottoa itse kohteesta. Kyseessä on monimutkainen halun tuottamisen rituaali, joka kohdistuu niin kohteeseen kuin tekijään, niin kuvan subjektiin kuin sitä reflektoivaan objektiin.”

Annika von Hausswolffin uusi teossarja saa aikaan kaksiosaisen liikkeen. Se esittää hyvin huolella ja intohimoisesti suoritetun välineen genealogian; hyvin henkilökohtaisesta ja sitoutuneesta näkökulmasta, samalla kuvaten erään teollisen muodon katoamista. Ja tämä tavalla, jossa kiintymys ja antaumus teemojen käsittelyyn välttää kaikenlaisen yksisuuntaisen instrumentalisoinnin, huvittavan nostalgian tai halvan sentimentaalisuuden.

Näyttelyn teokset tukevat ja tönivät, ne kutsuvat luoksensa ja työntävät välittömästi pois – saaden aikaan vuorovaikutuksen kuvan ja katsojan välillä. Kyse on teoksista, jotka saavuttavat sen kaikkein tärkeimmän mitä miltä tahansa taideteokselta voi vaatia: ne muistuttavat meitä siitä, mitä tarkoittaa olla elossa ja liikkeessä – aina ja alati, nautinnollisesti ja sisukkaasti kaikkia vastoinkäymisiä ja vastenmielisiä vedätyksiä vastaan potkien ja tapellen, potkien ja tapellen.

Lainaukset Mika Hannula ja Annika von Hausswolffin välisestä keskustelusta

Annika von Hausswolff on ruotsalainen vuonna 1967 syntynyt taiteilija, joka valmistui kuvataiteilijaksi 90-luvun puolivälissä. Annika von Hausswolff tutkii visuaalisia strategioita valokuvan alalla ja on osallistunut lukuisiin ryhmänäyttelyihin, pitänyt monia yksityisnäyttelyjä Euroopassa ja Pohjois-Amerikassa, esim. It All Ends With a Beginning ARoS Århusin taidemuseo, 2013 ja Ich bin die Ecke aller Räume, Magasin 3 Tukholma ja Turun taidemuseo, 2008. Hänen teoksensa käsittelevät eksistentiaalisia ja tilallisia kysymyksiä käsitteellisellä mutta samanaikaisesti valokuvalle ominaisella tavalla. Viimeiset viisi vuotta hän on toiminut professorina valokuvauksen maisteriopiskelijoille Göteborgin yliopistossa Ruotsissa. Hänen teoksiaan on kaikissa keskeisissä pohjoismaisissa museoissa.

Helsinki Contemporary har glädjen att presentera den svenska konstnären Annika von Hausswolffs första utställning på galleriet. Namnet på utställningen, Time Out Photography and About, både beskriver och definierar på ett karakteristiskt sätt innehållet i den helt nya verkserien.

I den här utställningen fokuserar Annika von Hausswolff på det brännande ämnet samtida bildproduktion, genom att i sina verk konfrontera några existentiella och djupgående frågor: vad handlar fotografi om? Och hur fortsätter vi att skapa bilder efter att ha övergått från analog till digital teknologi?

”Reflektioner över bildproduktionens redskap har alltid sysselsatt mig, ända sedan jag började med fotografi. Övergången från analog teknik till dess digitala efterföljare har förstås ökat behovet av att förstå utvecklingen av vår visuella kultur. Medan jag har studerat vissa verktyg som används för att på analogt vis göra bilder, men också vissa nyckelaspekter på själva fotografiet- till exempel dess förmåga att spegla verkligheten- har jag gjort en serie av bilder som alla, på ett eller annat sätt, har att göra med det analoga bildskapandet. Endel arbeten, som kontaktkartorna med ljus, har en mycket konceptuell utgångspunkt, medan andra – till exempel självporträttet - handlar mera om sambandet mellan fotografiet och döden.”

Med sin nya serie återupptäcker Annika von Hausswolff bokstavligen de yrkesredskap som var centrala i den analoga fotografiprocessen. Hon har producerat bilder eller objekt utgående från de här materialen som inte längre används. Med den ”poetiska rättvise-” strategi hon har valt har hon gett dessa närmast historiska föremål ett nytt liv som inte kan reduceras till deras ursprungliga funktion, hon har istället gett dem en helt ny temporalitet och textualitet – för att inte glömma sensibilitet.

”Det är omöjligt att föreställa oss vår existens idag utan möjligheten till att representera världen runt omkring oss. Indexikaliteten som är så typisk för den fotografiska tekniken är unik, och även om vi förstår mer och mer av hur den påverkar med verkligheten, utgör den fortfarande samma kraftfulla redskap för att presentera, representera, informera och spegla våra liv och vårt utrymme.”

”För en konstnär är integriteten allt. Antingen handlar det om hastighet, eller om långsamhet. För mig kommer idéerna blixtsnabbt, men sedan kan det ta år att förverkliga dem. När bilderna/idéerna blir offentliga, börjar de existera med en annorlunda logik som jag inte längre deltar i. Det är som att skära av sina fingrar, igen och igen.”

”Jag tror att hela den fotografiska apparaten är mättad av begärets mekanismer. När man avbildar någonting finns det en rörelse där man kommer närmare, samtidigt som man distanserar sig från temat. Det är en komplex ritual som går ut på att man skapar begär både inom det bevittnande subjektet och det reflekterande objektet.”

Den här verkserien uppfyller åter igen denna dubbla uppgift. Den visar upp en mödosamt och korrekt genomförd genealogi över ett medium, ur ett mycket personligt och engagerat perspektiv, medan den definitivt avbildar en industris nedgång. Samtidigt uppnås detta genom ett bestämt och hängivet reflekterande, som saknar varje spår av enkelriktad instrumentalisering, dum nostalgi eller billig sentimentalitet.

Tvärtom är det en verkserie som bränner och helar, skuffar och drar, smeker och samtidigt inte kunde bry sig mindre. Det är en serie som gör det ultimata vi kan be konstverk om: den påminner oss om vad det betyder att vara vid liv, sprattla och sparka - sparka med liv och lust och bestämdhet mot motgångarna.

Citaten är ur ett samtal mellan Mika Hannula och Annika von Hausswolff

Annika von Hausswolff är en svensk konstnär som föddes 1967 och genomförde sina regelrätta konststudier under mitten av 90-talet. Genom att utforska olika visuella strategier inom fotokonsten, har hon deltagit i många grupputställningar och hållit många separatutställningar i Europa och Nordamerika, till exempel It All Ends with a Beginning på ARoS Aarhus Kunstmuseum, 2013, och Ich bin die Ecke aller Raüme, på Magasin 3, Stockholm, och på Åbo konstmuseum, 2008. Hennes arbeten kretsar kring existentiella och rumsliga teman på ett konceptuellt och ändå formellt sätt. De senaste fem åren har hon varit professor för magisterstuderandena i fotografi på Göteborgs universitet i Sverige.

Share this exhibition