With her first solo show at Helsinki Contemporary, the Berlin-based painter Stefanie Gutheil gives us a taste of honey. Honey – the organic, fluid and warmth-inducing substance of honey, understood and seen as a symbol for the act of painting that perfectly well knows where it's coming from, and an act that just as perfectly well manages to articulate a physically and visually attractive contemporary version.

What we see is painting in action. It is taking place right here, right now, dealing with the massively overblown visual information which confronts and surrounds all of us, day in, day out. Gutheil faces this challenge head-on, and with verve. She takes no prisoners, so to speak, when and while these paintings shape the sense of reality we tremble before and deal with. When Die Stimmung is correct, nothing, nothing can beat this feeling.

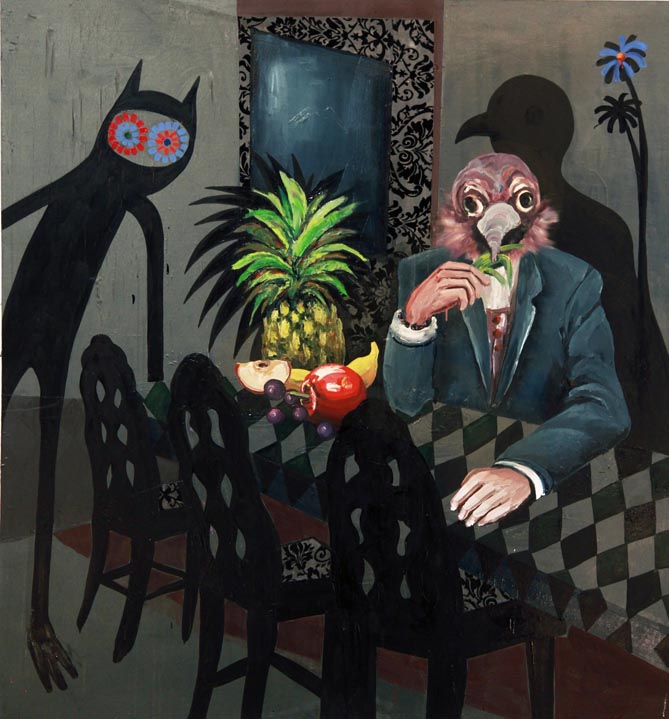

This is painting as a conscious continuation of the expressive mode, taking us on a tour de force via the German masters of the 1920s and 1930s, all the way to classical painters like Hieronymus Bosch and Diego Velasquez. It is always, constantly boiling over and freezing over. It is a process that definitely stays far, far away from the closing doors of neat and tidy harmony. This is where the weirdness of the boring everyday meets scary monsters and animal-like figures: they shake hands furiously and provide fabulous connotations of imaginary conflicts – and, let us not forget, caressing acts.

They create sensualities and sensibilities that do not merely break even. They become more, much more than we could expect. Like the title of the show – menschenschattenwesending, which translates as the poetic near nonsense combination of people, shadows, essence and things – they add the sharp edge of the unknown but yet expected to the mix, the sweet and tender suspense of the things to come.

With Gutheil, these sensualities and sensibilities turn into paintings, like caterpillars that turn into butterflies, colourful and playful takes on our hybrid realities, articulating the strongly lived-through and felt co-existence of mixed worlds and sensations.

“There is a valid reason for mixing different and seemingly absurd elements with each other. This is clear in the case of painting a figure. If the figure would be, let’s say, only a human being, I would so easily get stuck in the game of representation – as in the question does it look like the type of a human being it is supposed to look like, or not. It is the honest dilemma of what is the role and place for a figure in a painting that is not abstract and not realistic. The question being: if it is not this or that, what is it then?”

“When I mix these things, and the figure of a person is a mix of human and animal tendencies and features, it is impossible to step back and question, or to think whether this is realistic or representational. It turns into something different, something else. For me, it signifies the move from illustration towards doing a painting – and doing this with the means that are available for my type of painting.”

“The idea that I have is to bring together elements and issues, whatever they are, in the visual field, and kind of force them together, carefully and caressingly – showing that at least in the realm and reality of a painting, they actually not only fit but do, in fact, really belong next to one another, that these seemingly paradoxical parts need to be and belong together.”

Quotes from a discussion between Stefanie Gutheil and Mika Hannula

Berliiniläistaiteilija Stefanie Gutheilin ensimmäinen yksityisnäyttely Helsinki Contemporaryssa on maalausta itsessään ja parhaimmillaan. Se on maalausta aistillisena ja kehollisena, viileänä ja villinä läsnäolona. Se on kuin visuaalista hunajaa – orgaanista, lämpöä ja lempeä tuottavana hyvinkin viettelevänä ja viekkaana olemuksena. Maalauksellisena tekona, joka on tarkasti tietoinen omasta perinnöstään kuin myös mahdollisuuksista maalauksen fyysiseen ja henkiseen tämänhetkiseen artikulointiin.

Stefanie Gutheilin kohdalla katsomme maalausta liikkeenä – ja liikkeessä. Se on maalausta, joka aktiivisesti hakee suhdettaan ympäristöön, erityisesti meitä kaikkia koskettavan tiedon ja kuvamateriaalin vyöryn kautta. Gutheil kohtaa tämän viriketulvan aiheuttaman haasteen ja hän kohtaa sen vauhdilla ja voimalla. Hän ei epäile, ei kysy lupaa, eikä ainakaan pyydä anteeksi. Hän suodattaa ja suojaa, muuntaa ja muokkaa. Gutheil antaa mennä – ja menee itse perässä saaden aikaan hyvin omaperäisen ja viehättävän tavan tehdä maalausta.

Kyse on maalauksesta, joka asettuu suoraan jatkumoon ekspressiivisen tyylin kanssa, vieden meidät mukaansa suurelle matkalle, jossa käymme kylässä 1900-luvun alkupuolen saksalaisten mestareiden luona ja jatkamme matkaa aina klassisiin tekijöihin, kuten Hieronymus Boschiin ja Diego Velasqueziin.

Se on maalausta, joka ei koskaan taivu tasan, se ei pysähdy raameihin, ei figuuriin. Se menee ja tulee yhtäaikaisesti yli ja ali, pysyen hyvinkin hanakasti erossa kaikenlaisesta tasapäisyydestä ja sisäsiististä. Näissä maalauksissa arjen armollinen omituisuus kohtaa eläinhahmojen pelottavan fantasian. Ne kohtaavat, kättelevät ja saavat aikaan konnotaatioiden myllerryksen, jossa olennaista on mennä mukaan, osallistua vauhdin luomiseen ja äkkivääriin pysähdyksiin, mutta myös muistaa pitää tiukasti kiinni siitä huivista.

Tuloksena sarja maalauksia, jotka ovat enemmän, paljon enemmän kuin osaisimme odottaa. Pääsemme lähelle sensuaalisuutta ja tunneherkkyyttä, joka näyttelyn nimen mukaisesti menschenschattenwesending - kääntyy yhdistelmäksi ”ihmiset, varjot, oliot ja asiat” – tuo aina ja alati yhtälöön, siihen kohtaamiseen kera, maalauksen elementtejä, joista osan me tunnemme ja tunnistamme, mutta joista osat ovat täynnä oikullisia ja ovelia jännitteitä.

Gutheilin kohdalla tämä jännite, vuoroveto oletusten ja kokemuksen välillä, muokkaantuu maalaukseksi, jossa vastakohdat eivät hyljeksi vaan halaavat toinen toisiaan, luoden maalauksen tilan ja tilaisuuden, joka on monta ja monessa, hybridi-identiteetti täynnä ristiriitaisia mutta nautinnollisia täsmällisyyksiä – tapauksia, joista tulee se yksi, se singulaari, se tietty ja tämä.

“On olemassa validi syy erilaisten ja näennäisesti absurdien elementtien sekoittamiseen. Tämä on selvää hahmon maalauksen kohdalla. Jos hahmo olisi, sanotaan vaikka, ainoastaan ihminen, jumittuisin helposti esittämisen peliin – kuten kysymykseen; näyttääkö se sellaiselta ihmiseltä, jolta sen on tarkoitus näyttää, vai ei. Kyseessä on rehellinen dilemma siitä, mikä on hahmon rooli ja paikka maalauksessa, joka ei ole abstrakti eikä realistinen. Kysymys kuuluu: jos se ei ole sitä tai tätä, niin mitä se sitten on?”

“Kun sekoitan nämä asiat, ja hahmo on sekoitus ihmisen ja eläimen taipumuksia ja piirteitä, on mahdotonta astua taaemmas ja kyseenalaistaa tai ajatella, onko tämä realistinen vai kuvaava. Se muuttuu joksikin erilaiseksi, joksikin muuksi. Minulle tämä tarkoittaa siirtymää kuvittamisesta maalauksen tekemiseen – ja tämän tekemistä keinoilla, joita on tarjolla minunlaiselleni maalaamiselle.”

“Ajatukseni on tuoda yhteen elementtejä ja ongelmia, mitä ne ikinä ovatkaan, visuaalisella kentällä, ja ikään kuin pakottaa ne yhteen, varovaisesti ja hellästi – näyttääkseni, että ainakin maalauksen alueella ja sen todellisuudessa ne itse asiassa eivät ainoastaan sovi, vaan suorastaan kuuluvat yhteen, että näiden näennäisesti paradoksaalisten osien täytyy ja kuuluu olla yhdessä.”

Lainaukset keskustelusta Mika Hannulan kanssa

Den första separatutställningen på Helsinki Contempoarary av den berlinbaserade konstnären Stefanie Gutheil är måleri i sig och som bäst. Det är måleri som sensuell och kroppslig, som sval och vild närvaro. Det är som visuell honung – organiskt, värme- och kärleksingivande, väldigt förförande och lömskt. En målningsakt, som är utmärkt väl medveten om var den kommer ifrån och likaså om möjligheterna till det rådande målandets fysiska och psykiska artikulation.

I Stefanie Gutheils fall observerar vi målningen som en rörelse - och i rörelse. Det är målning, som aktivt söker relationen till omgivningen, speciellt via informations- och bildflödet, som berör oss alla. Gutheil möter den här utmaningen orsakad av stimulansflödet och hon möter den med hastighet och kraft. Hon tvekar inte, frågar inte om lov och ber framförallt inte om ursäkt. Hon filtrerar och skyddar, förändrar och bearbetar. Gutheil släpper loss – och följer själv efter, skapande ett väldigt originellt och fötrjusande sätt att måla.

Det är frågan om måleri, som utgör en direkt fortsättning på den expressiva stilen, som tar oss med på en hisnande resa via de tyska mästarna från början på 1900-talet, hela vägen tillbaka till klassiska målare som Hieronymus Bosch och Diego Velázquez.

Det är måleri, som aldrig går jämnt ut, som aldrig stannar innanför ramerna eller i figuren. Det kommer och går samtidigt över och under, det stannar långt ifrån all sorts jämställdhet och rumsrenhet. Det är här som det underliga i den skonsamma vardagen möter den skrämmande fantasin av djurliknande figurer. De möter, skakar hand och åstadkommer ett virrvarr av konnotationer. Det är väsentligt att gå med, att delta i ökandet av farten och i de tvära bromsningarna, men också att komma ihåg att hålla ett hårt tag om den där scarfen.

Resultatet är en serie målningar, som är mera, mycket mera än vi kunde vänta oss. Vi närmar oss sensualitet och sensibilitet, som enligt namnet på utställningen menschenschattenwesending – som översatt utgör kombinationen “människor, skuggor, varelser och ting” – alltid och ständigt tar oss till ekvationen, den med mötet med målningens element, där vi känner till och igen en del, men vars delar är fulla av besynnerliga och sluga spänningar.

I Gutheils fall förvandlas den här spänningen, växlingen mellan förmodan och erfarenhet, till målningar, där motsatserna inte stöter ifrån varandra utan kramar varandra, skapande utrymme och möjligheter i målningarna, som är många och i många, en hybrid identitet full av kontroversiell men njutningsfull precision – fall som blir ett, singularet, just det specifika.

”Det finns en giltig orsak till att blanda skilda och skenbart absurda element med varandra. Det här är självklart då man målar en figur. Om figuren vore, ska vi säga, enbart en människa, skulle jag så lätt fastna i spelet av representation – som frågan om den ser ut som den människa den ska likna, eller inte. Det är frågan om ett uppriktigt dilemma, som handlar om vilken är rollen och platsen för en figur i en målning, som inte är abstrakt eller realistisk. Frågan lyder: om den varken är det här eller det där, vad är den då?”

”När jag blandar ihop dessa saker, och figuren blir en blandning av mänskliga och djuriska tendenser och drag, är det omöjligt att ta ett steg tillbaka och ifrågasätta eller tänka om det är realistiskt eller representerande. Den förvandlas till något annorlunda, något annat. För mig betyder det att förflytta mig från att illustrera till att måla – och att göra detta med de medel som är tillgängliga för mitt sätt att måla.”

”Idén jag har är att föra samman element och problemställningar, vilka de än är, på det visuella fältet, och liksom tvinga dem ihop, försiktigt och smeksamt – och visa att i alla fall inom målningens område och verklighet passar de egentligen inte bara in, utan faktiskt hör hemma bredvid varandra, att dessa skenbart paradoxala delar måste finnas till och hör ihop.”

Citaten ur en diskussion mellan Stefanie Gutheil och Mika Hannula

Share this exhibition