With those words the artist Ville Andersson describes the starting points for his new exhibition. The title of the show opening at Helsinki Contemporary 12 January, I can’t go on. I will go on., is adapted from the last words of Samuel Beckett’s novel The Unnamable. Andersson sees this phrase as reflecting an environment, which is simultaneously tragic and comic. Tragic because it is disintegrating, comic because it keeps on going. At the same time, the words sound like a motivational-quotation-like mantra.

The exhibition had its beginnings in a photograph taken in a desert in New Mexico. The desert is nowadays the home of the Lincoln Near-Earth Asteroid Research project, which observes asteroids that pass close to the earth. The world’s first nuclear test was carried out nearby. In Curiosity the desert becomes timeless and placeless. Andersson is interested in such non-places, which are not just a matter of the absence, but also of the presence of absence. Not of that which is not there, but more a contemplation of what has been or what will be.

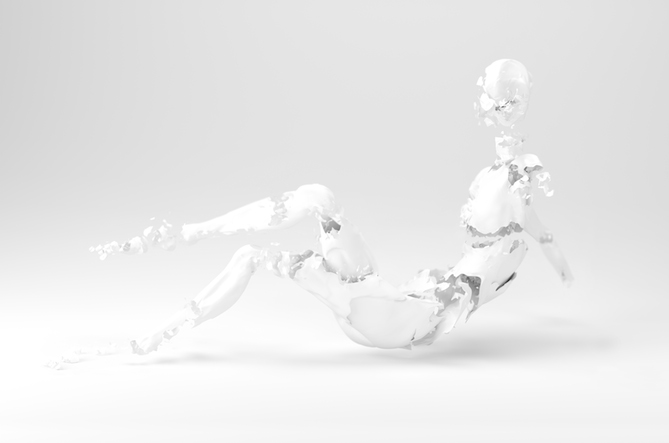

The exhibition will include photographs, drawings and paintings. Andersson has applied a new technique, which might be called ‘digital sculpture’. He has used 3D-modelling software to create images that have ultimately been printed like photographs. The works shift between abstract and figurative, organic and inorganic.

One element of the works is landscapes. These formations reminiscent of mountains and stone have come about from memory. They are residual recollections, ephemeral nuggets of experience. The working process is perhaps not so much a matter of simplification, as of a suspension of reduction. Another theme is the body and the face. The genderless figures seem to be in motion, and yet at the same time static. Andersson speaks of the consolation of movement: play or dance are attempts to transcend tragedy, to tend a wound, and to create meanings.

Characteristic features of Andersson’s aesthetic are allusiveness, richness of nuance, precision, understatement and ephemerality. He combines themes and creates links between things. In addition to the flow of ideas, he is interested in the silence that is a silencing not only of sounds, but also of the Self.

Along with the exhibition, a catalogue of Andersson’s recent production will be published together with the Finnish Institute in Germany. After the exhibition at Helsinki Contemporary, Andersson's new works will be shown in a solo exhibition at the Institute in Berlin from 9 March to 25 May and later the same year at LOKO Gallery in Tokyo. Andersson is one of the artists selected for the Artist-in-Residence program at The Watermill Center, New York for 2018. He will be staying and working at Watermill in March-April.

Ville Andersson (b. 1986 in Pernaja) lives and works in Helsinki, Finland. In 2015 he was named the Young Artist of the Year in Finland, one of the biggest and best known Finnish art awards. He had two solo museum exhibitions the same year. Andersson has exhibited actively, including at: EMMA – Espoo Museum of Modern Art; National Art Center, Tokyo; Vitraria Glass + A Museum, Venice; Museum Weserburg, Bremen; The Centre for Photography, Stockholm; FOMU – Fotomuseum, Antwerp. Andersson’s works are represented in several public collections, including Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art, Saastamoinen Foundation Art Collection, the Amos Anderson Art Museum and the Jenny and Antti Wihuri Foundation Collection. Recent projects include stamps for the Finnish postal service, tableware for the company Arabia and set and costume design for a theatre play.

Thank you to the Finnish Institute in Germany, Svenska kulturfonden and the graphic designer of the catalogue Hennamari Asunta.

”Aavikon keskeltä, armottoman auringon paahteen ja myrskyjen yrittäessä tyhjentää kaiken, löytyi myös hieman kasvillisuutta. Vastoin mielikuvaa siitä katovaisuuden symbolina, nuo harvat pienet kukat muuttuivat koskemattomiksi ja elämää affirmoiviksi elementeiksi.”

Näin sanoin taiteilija Ville Andersson kuvailee uuden näyttelynsä lähtökohtia. Helsinki Contemporaryn kevään avaavan näyttelyn nimi, I can’t go on. I will go on., on mukaelma Samuel Beckettin The Unnamable -romaanin viimeisistä sanoista. Andersson näkee ilmaisun heijastavan ympäristöä, joka on samanaikaisesti traaginen ja koominen. Traaginen koska se murenee, koominen koska se jatkaa menoaan. Samalla sanat näyttäytyvät motivaatiositaatin kaltaisena mantrana.

Näyttely sai alkunsa New Mexicon aavikolta otetusta valokuvasta. Aavikko on nykyisin koti Lincoln Near-Earth Asteroid Research -projektille, joka havainnoi maata lähestyviä asteroideja. Maailman ensimmäinen ydinkoe tehtiin lähialueella. Teoksessa Curiosity aavikko muuttuu ajattomaksi ja paikattomaksi. Anderssonia kiinnostaa tämänkaltaiset epäpaikat, joissa ei ole kyse pelkästään ajan ja paikan poissaolosta, vaan myös poissaolon läsnäolosta. Ei siitä mitä ei ole, vaan pohdinta siitä mitä on ollut tai tulee olemaan.

Näyttelyssä nähdään valokuvaa, piirustusta ja maalausta. Andersson on käyttänyt uutta tekniikkaa, jota voisi kutsua digitaaliseksi veistämiseksi. 3D-mallinnusohjelman avulla taiteilija on luonut kuvia, jotka lopulta on vedostettu valokuvan tapaan. Teokset liikkuvat abstraktin ja esittävän, orgaanisen ja epäorgaanisen välissä.

Yhtenä elementtinä teoksissa ovat maisemat. Vuoria ja kiveä muistuttavat muodostelmat ovat syntyneet muistin pohjalta. Ne ovat jäljellä olevia muistoja, katoavaisia kokemuksen hippuja. Työskentelyssä kyse ei ehkä olekaan pelkistämisestä vaan reduktion pysäyttämisestä. Toisena aiheena on keho ja kasvot. Sukupuolettomat hahmot vaikuttavat olevan liikkeessä, mutta samaan aikaan pysähdyksissä. Andersson puhuu liikkeen lohdusta: leikki tai tanssi on yritys ylittää tragedia, hoivata haavaa ja luoda merkityksiä.

Anderssonin estetiikan ominaispiirteitä ovat vihjailevuus, nyanssirikkaus, tarkkuus, vähäeleisyys sekä katoavaisuus. Hän yhdistelee aiheita ja luo linkkejä asioiden välille. Ajatusvirran lisäksi häntä kiinnostaa hiljaisuus, joka ei ole ainoastaan äänten, mutta myös Minän hiljentämistä.

Näyttelyn yhteydessä julkaistaan katalogi taiteilijan viime vuosien tuotannosta yhteistyössä Saksan Suomen-instituutin kanssa. Helsinki Contemporaryn näyttelyn jälkeen Anderssonin uusia teoksia nähdään yksityisnäyttelyissä instituutin galleriassa Berliinissä 9.3.–25.5. ja myöhemmin kuluvana vuonna LOKO Galleryssa Tokiossa. Andersson on yksi The Watermill Centerin Artist-in-Residence -ohjelman taiteilijoista vuodelle 2018. Hän työskentelee Watermillissä New Yorkissa maalis-huhtikuussa.

Ville Andersson (s. 1986, Pernaja) asuu ja työskentelee Helsingissä. Andersson nimettiin vuoden nuoreksi taiteilijaksi 2015. Palkintoon sisältyi laaja julkaisu sekä yksityisnäyttelyt Tampereen taidemuseossa ja Aboa Vetus & Ars Novassa Turussa. Anderssonin teoksia on esitetty laajalti Suomessa ja ulkomailla, mukaan lukien EMMA – Espoon modernin taiteen museo; The National Art Center Tokiossa; Vitraria Glass +A Museum Venetsiassa; Weserburg Museum für Moderne Kunst Bremenissä, Saksassa; Centrum för Fotografi Tukholmassa; ja FOMU – Fotomuseum Provincie Antwerpen, Belgiassa. Anderssonin teoksia on mm. Saastamoisen säätiön, Nykytaiteen museo Kiasman, Amos Anderssonin taidemuseon, Pro Artibuksen ja Jenny ja Antti Wihurin rahaston kokoelmissa. Taiteilijan viimeaikaisiin projekteihin lukeutuu Postin Art Post II -postimerkkisarja, astiaston kuosin suunnittelu Arabialle, sekä Klockriketeaternille toteutettu teatterinäytelmän lavastus ja puvustus.

Med dessa ord beskriver konstnären Ville Andersson utgångspunkterna för sin nya utställning. Utställningen som samtidigt öppnar Helsinki Contemporarys vårsäsong har titeln I can’t go on. I will go on., en parafras på de sista orden i Samuel Becketts roman The Unnamable. Andersson ser i uttrycket en syftning på en miljö som är både tragisk och komisk på en och samma gång. Tragisk för att den bryts ned, komisk för att den fortsätter som förr. Samtidigt framstår orden som ett mantra, ett slags motivationscitat.

Utställningen initierades av ett fotografi från öknen i New Mexico. Öknen är numera hemvist för projektet Lincoln Near-Earth Earth Asteroid Research som observerar asteroider som närmar sig jorden. Världens första kärnsprängning utfördes i dessa trakter. I verket Curiosity förvandlas öknen till någonting tid- och platslöst. Andersson fascineras av sådana icke-platser där det inte handlar enbart om frånvaro av tid och plats, utan också om frånvarons närvaro. Inte om vad som inte är, utan tankar kring vad som har varit eller kommer att vara.

På utställningen visas fotografier, teckningar och målningar. Andersson har använt ny teknik som kunde beskrivas som digital skulptur. Med ett 3D-modelleringsprogram har han skapat bilder som han sedan gjort utskrifter av på samma sätt som av fotografier. Verken rör sig mellan det abstrakta och det föreställande, mellan det organiska och det oorganiska.

Landskap är ett återkommande element i verken. De berg- och stenlika formationerna har konstnären skapat ur minnet: kvarblivna minnesbilder, erfarenhetens förgängliga smulor. Arbetet handlar kanske inte om att renodla och förenkla, utan om att avbryta reduktionen. Ett annat motiv är kropp och ansikte. De könlösa figurerna tycks vara i rörelse samtidigt som de ändå står still. Andersson talar om trösten i rörelsen: lek och dans är försök att komma över en tragedi, plåstra om ett sår, skapa betydelser.

Utmärkande för Anderssons estetik är allusion, nyansrikedom, noggrannhet, stramhet och förgänglighet. Han kombinerar motiv och skapar länkar mellan olika fenomen. Förutom tankeström intresserar han sig för tystnad, som då inte syftar på att dämpa endast ljud, utan även Jaget.

I samband med utställningen publiceras en katalog över Anderssons produktion under de senaste åren. Samarbetspartner för katalogen är Finlandsinstitutet i Tyskland. Efter utställningen på Helsinki Contemporary visas nya verk av Ville Andersson på en separatutställning i institutets galleri i Berlin 9.3–25.5 och senare samma år på LOKO Gallery i Tokyo. Andersson är en av konstnärerna inom The Watermill Centers residensprogram Artist-in-Residence för 2018 och han kommer att arbeta i Watermill, New York i mars-april.

Ville Andersson (f. 1986, Pernå) bor och arbetar i Helsingfors. Han utsågs till Årets unga konstnär 2015. I priset ingick en omfattande publikation samt separatutställningar på Tammerfors konstmuseum och Aboa Vetus & Ars Nova i Åbo. Anderssons verk har visats rikligt både i Finland och utomlands, bland annat på EMMA – Esbo moderna konstmuseum; The National Art Center i Tokyo; Vitraria Glass +A Museum i Venedig; Weserburg Museum für Moderne Kunst i Bremen, Tyskland; Centrum för Fotografi i Stockholm; samt FOMU – Fotomuseum Provincie Antwerpen, Belgien. Hans verk ingår i bland annat Saastamoinenstiftelsens, Museet för nutidskonst Kiasmas, Amos Anderssons konstmuseums, Pro Artibus samt Jenny och Antti Wihuris stiftelses samlingar. Bland Anderssons senaste projekt kan nämnas Postens frimärksserie Art Post II, mönstret till en servis för Arabia samt scenografi och dräkter för en pjäs på Klockriketeatern.

Vi tackar: Finlandsinstitutet i Tyskland, Svenska kulturfonden samt Hennamari Asunta för katalogens grafiska form.

Share this exhibition